Michelle Cliff (Nov. 2, 1942-June 12, 2016) was an award-winning Jamaican novelist, essayist, critic, poet, scholar, and teacher. An influential author in Caribbean, feminist, and lesbian writings, some of her notable works include: Abeng, No Telephone to Heaven, Claiming an Identity They Taught Me to Despise, Free Enterprise, If I Could Write This In Fire, and The Land of Look Behind. Cliff's work reflected many parts of her identity, contemporary sociopolitical concerns stemming from colonialism, and a critical investment in the Caribbean and her diasporas. Her works examine the complexities of identity politics, lesbianism, colorism, colonialism/post-colonialism and revolution – both of the personal variety and the political. On June 22, 2017, we gathered at the Caribbean Philosophical Association Annual Meeting in NYC to honor her life and writing. This post includes the work of the roundtable participants. The roundtable, titled "'Writing in Fire': Honoring the Life & Legacy of Michelle Cliff" marked the second year that the Chair of Afro-Diasporic Literatures (me) and the Chair of the Initiative on Gender, Race, and Feminisms (Xhercis Mendez) joined together to propose roundtables to honor Caribbean women writers at the CPA (at the 2016 we celebrated the 10th/11th publication anniversary of M. Jacqui Alexander's Pedagogies of Crossing). This year two Ph.D. students - Keishla Rivera (Rutgers Newark) and Briona Jones (Michigan State) - joined moderator Xhercis Mendez and I to reflect on the rich inheritance Michelle Cliff has left us. Below are excerpts from the reflections which engendered a powerful and generative dialogue across several topics, fields, and interests. Michelle Cliff, Presente!

Reflection I: On Fiction As History

[Yomaira C. Figueroa, Assistant Professor, Michigan State University]

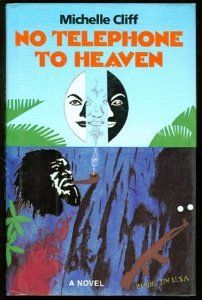

In her 1994 article, “History as Fiction, Fiction as History” Michelle Cliff asks, "How do we capture the history that remains only to be imagined?" Cliff is a textbook Caribbeanist, her work writes back to colonialism, to slavery, to the abyss, and it imagines new ways of being and knowing across untold histories of diaspora and decolonial struggles. Her essay “Journey into Speech” is a meditation on “a past bleached from our minds." She argues that this problematic of erasure, “means re-creating the art forms of our ancestors and speaking in the patois forbidden us. It means realizing our knowledge will always be wanting. It means also, I think, mixing in the forms taught us, undermining the oppressors language and co-opting or corrupting his style and turning it to our purpose.” This mixing of form, represents a turn to re-creating forms of speech and modes of knowledge and is what inspired her landmark novel No Telephone to Heaven.

Cliff builds up her work through an attentiveness to spatiality and temporality – what she calls “sites of memory.” No Telephone to Heaven for example is concerned with anti-colonial and revolutionary politics in 1970s Jamaica. It is predicated on ruination- the expansive overgrown and wild plots of Jamaican land that were once plantations. In it, a young Clare Savage is torn between worlds (Jamaica, US, England / class stratification/racism in Jamaica), and finds herself to be a motherless daughter in a motherless nation. When writing about the Caribbean she is deeply tied to the land. When writing about the U.S. she reflects on untold histories. For example, her novel Free Enterprise takes up the life of Mary Ellen Pleasant, an 19th century Black abolitionist and entrepreneur - who strategically passed for white but was known in the Black community as a Black woman. Pleasant is known as the mother of Civil Rights in San Francisco, CA and her life of passing and political power was of much interest to Cliff. This preoccupation with passing, skin color, and privilege is reflected in much of Cliff's writing: “we were colorists and we aspired to oppressor status,” she writes in the essay "If I Could Write This In Fire" about her own family in 1950s/1960s Jamaica. Cliff is one of the richest contributors to the poetics and politics of identity politics. Despite the fact that “identity politics” are constantly undermined, undervalued and under-attack, the oeuvre of her work underscores its usefulness, its necessity. She unravels the trappings of white supremacy, puts it on display and destabilizes it.

In her essay “In My Heart A Darkness” she examines how, “the template cut by the white imagination – European or American – cannot accommodate [her] appearance, speech patterns, or intellect as a West Indian.” She does not "look Jamaican", she does not "speak like a Jamaican", etc. For the racist imagination she is an impossibility. As an Afro-Puerto Rican in diaspora, born 40 years after Cliff, this resonantes deeply for I too disrupt the white imagination. My Blackness, Puerto Ricanness, accented speech, etc. do not compute. Cliff tells us that “when the white imagination is disrupted by matters of race, it becomes agitated. Its sense of neatness is disturbed. When the Other appears to be the One. Apocalypso.” In other words, Cliff's presence itself implodes the white imagination - she is (we are) the proof-in-flesh of so many untold histories. In spring 2017, my Poetics of Liberation and Relation graduate seminar had an hour-long discussion on this one sentence across a series of scenarios. Cliff provides a rich terrain indeed.

By building transnational discourses in poetry, prose, and fiction, Cliff is able to showcase the complexities of being a fair skinned Jamaican in the US, a fair-skinned Jamaican amongst a host of color stratified societies (including Jamaica where she discusses the division of labor and domestic reproduction and in South Africa where she links Apartheid with the US prison industrial complex). Some of her most well known essays are reflections on road trips and travels she took in the US during the 1980s and 1990s. She documents conversations at universities, museums, plantations, gas stations, and in cabs. She questions the absence of memory, indicting the forgetfulness and shorthand that are used under the guise of brevity. In critiquing academic discourses around "multiculturalism" she notes, “I am weary of the shorthand which passes for cultural commentary, political awareness in these times. Why can't we use more words? Why can't we take the time to say what we mean? Why must the complexity of America always be reduced to simplicity?”

What Cliff produced in her 40+ years of writing was an attempt at battling simplistic discourse that obfuscated the complexities of the Caribbean and her diaspora, of race and sexuality, and of history and memory. For Cliff the Caribbean was a place of contradiction, fragmentation, and love. To excavate unheard histories and to think of liberation she wielded those same tools: contradiction, fragmentation, and love. “We are fragmented people. My experience as a writer coming from a culture of colonialism, a culture of Black people riven from one another, my struggle to achieve wholeness from fragmentations while working within fragmentation producing work which may find its strength in its depiction of fragmentation, through form a well as content is similar to other writers whose origins are in countries defined by colonialism.” This is a women of color politic, it is a practice of relationally – where she finds possibilities, parts of her own story, and Caribbean history, in the work of others – for example reading the work of African, US, South Asian, Middle Eastern and other writers of color and recognizing their contributions to liberatory discourses and modes of resistance. Her feminist and lesbian politics were also central to how she imagined Caribbean liberation. Cliff’s practice of reading other novelists generously is a methodology of which to take hold. She builds on/around/with these works - including Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy, and the work of Toni Morrison, Aurde Lorde, Derek Walcott, Aimé Césaire, Édward Kamau Brathwaite and others.

Cliff’s work is a kind of extended release potion. It is work that works slowly and efficiently on the reader who is compelled to turn the mirror and meditate on herself. As a diasporic colonial subject, I find myself hailed by both her criticism of colonialism and failures of post colonialism, but also by how she underscores how we are intimately affected by its attempt to disaffect us and to disarm us. She resisted this and her work arms us with tools to resist this too. For example she tells us that: “The test of a colonized person is to walk through a shanty town in Kingston and not bat an eye. This I cannot do. Because part of me lives there- and as I grasp more of this part I realize what needs to be done with the rest of my life.” What Michelle Cliff did until the end of her life was write and capture histories and relations and capturing "the history that remains only to be imagined?”

To discuss Reflection I, please comment below or send me a message.